The Best of Times, The Worst of Times

Many manufacturers are feeling cautious about the economy and hesitant to make new investments until they get a better sense of certainty. But things are changing faster than ever now. Here are some industry forecasts about some market sectors that could be hot and others that may not.

Posted: October 28, 2016

Charles Dickens opened up his classic book “A Tale of Two Cities” with the famous opening, “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . .” as part of a universal approach that depicts the plight of the French peasantry being demoralized by the French government in the years leading up to the French revolution. That same universal opening – “it is the best of times, it is the worst of times . . .” – also reflects the current state of U.S. manufacturing today and its business outlook for the foreseeable future. It depicts the plight of shops both large and small that are learning how to compete while dealing with a number of massive economic shocks that are concentrated throughout market sectors and have not yet been fully dissipated.

To get our minds around the current state of manufacturing, let’s start by looking at “the best of times” that many shops now enjoy, then we’ll examine some of the shocks that are causing “the worst of times.”

THE BEST OF TIMES

There are two broad measures commonly used to measure manufacturing’s overall impact on our society. One is the proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) that manufacturing accounts for in our national economy. The other is the “multiplier effect,” which measures the impact of manufacturing on other industries from an increase in economic activity by a specific industry. As of this writing, government statistics state that manufacturing’s proportion of our nation’s GDP is about 11 percent. In other words, the annual value-added contribution of manufacturing to our economy, divided by the value of all goods and services produced in our country, stands at about 11 percent. So if our GDP in the U.S. is now around $17.4 trillion, then manufacturing alone accounts for a little over $1.9 trillion. That makes U.S. manufacturing – by itself – the eighth largest economy in the world, just behind India ($2.3 trillion) and just ahead of Italy ($1.8 trillion). That is huge, but that’s not all . . .

Let’s take a look at the manufacturing multiplier effect, which is another way estimating the sheer volume of all the stuff in our lives. We all know intuitively that our lives are surrounded by and completely reliant on thousands upon thousands of manufactured goods and services, whether we’re working, eating, driving, flying, sleeping, playing, or relaxing. The multiplier effect represents the impact of all of these things on our lives as an economic factor.

In April 2016, the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation (MAPI; Arlington, VA) analyzed national inter-industry input-output tables built by the University of Maryland to show that the multiplier effect of manufacturing is now 3.6. This means every dollar that manufacturing contributes to our GDP generates another $3.60 of value-added contributions in other industries elsewhere across the U.S. economy. In other words, the total value chain of manufacturing now accounts for about one-third of U.S. GDP, or around $6 trillion. This makes the total value chain of U.S. manufacturing – by itself alone – the third largest economy in the world, behind the entire nation of China ($11.4 trillion) and ahead of the entire country of Japan ($4.4 trillion). That is not huge, that is colossal!

Let’s get a bit more detailed so that we can fully understand the economic impact that the value chain of manufacturing has on our lives. The manufacturing value chain starts with all of the upstream activities associated with manufactured products that are used by factories to make and ship final products that are ultimately used by us when we work, eat, drive, fly, sleep, play, or relax. These activities include the value of all the intermediate inputs purchased for use in production, such as raw materials, process inputs, and services. So, for example, car manufacturers need steel from steel manufacturers to make the cars that we drive; the steel manufacturers need coal and iron ore from the mining industry to make the steel used by the car manufacturers; and all of these raw materials in their various forms must be transported from one place to another destination by using trucks, trailers, trains, ships and aircraft.

The value-added economic contribution of all of these intermediate inputs upstream of the factories that go into manufactured goods destined for final demand is estimated to be over $3 trillion. But that’s only the upstream portion of the chain that feeds into the factories.

As the goods move downstream from the factory loading docks through their sales chains, more contribution is generated by the transportation, wholesaling, and retailing of all the final goods that were shipped from the factories. More value-added contribution is generated by services related to these manufactured goods, such as rental, leasing, insurance, professional services, maintenance, and repair. Combine all of these values together and throw in the value-added contribution derived from manufactured imports, and the estimated value-added economic contribution generated by downstream activities adds another $3 trillion. This confirms that the combined value-added economic contribution of manufactured goods used for final demand in our country is estimated to be about $6 trillion, or roughly one-third of our total GDP.

So the bottom line here is the bottom line: manufacturing is the key driver of the U.S. economy, and these are the best times ever to be in the manufacturing business. That’s a brief profile of “the best of times” that manufacturers now enjoy. Now let’s examine some of the shocks that are causing “the worst of times” in U.S. manufacturing.

SHOCK TREATMENT

Over the past few months, economic issues in China, Europe and the Middle East have resulted in sluggish global economic growth, a strong U.S. dollar, weak agriculture, and even weaker oil and gas activity. Inside our country, very aggressive U.S. government policies on health care, environmental issues, wage laws and other reforms have unleashed an unprecedented deluge of taxes, regulations and unplanned expenses on American manufacturers that make it more difficult for them to remain competitive. Added to all of these issues is the rising uncertainty about a potential interest rate increase from the Federal Reserve, this year’s unusual presidential election and whether the next administration will be more or less friendly to business in our country.

All of this economic and political tension has generated a weak environment for manufacturing, with minimal to no gains in recent U.S. industrial production. Instead of growth, many manufacturers are moving to stabilize their operations to relieve a number of economic shocks that are concentrated in various market sectors they are competing in:

- Inventories are too high in some sectors. The inventory-to-sales ratio is still exceptionally high at many manufacturers and wholesalers. To pare inventories, manufacturers must reduce production relative to sales. In this slow-growth environment, production takes the brunt of the adjustment.1

- Excess inventories and cheap oil prices have led to disappointing profits, a somewhat unstable stock market and risk aversion to higher capital investments in all of these market sectors, all of which aggravate the unwillingness for more investment in manufacturing until after the presidential election has been decided.1

- Metal fabricators and other steel consumers have growing concerns about their competitiveness as costs for flat-rolled metal are rising substantially in the U.S. due to new anti-dumping duties on imported steel that are being finalized by the International Trade Commission. Resulting increases in material costs will significantly impact the competitiveness of steel consumers in the U.S.2

So some market sectors are performing well, while others are struggling. Automotive and aerospace, which mitigated the market decline for the last 15 months of the current downturn, continue to hold their own – but they aren’t growing. Other sectors are growing, such as consumer electronics, firearms, and medical, but those represent only 12 percent of the overall manufacturing industry. Many shops are reporting strong levels of quotation activity, but longer conversion rates for actual orders. For this reason, many manufacturers are resistant to make investments in capital equipment out of a sense of caution. This helps to explain why overall U.S. orders for metal cutting and metal fabricating machine tools dropped 24.8 percent in July 2016 (the latest report as of this writing) from the previous month and U.S. cutting tool orders slumped also, down 16.2 percent from the previous month.3

According to AMT – The Association for Manufacturing Technology (McLean, VA), the latest industry forecasts indicate that the capital manufacturing equipment market will remain in negative territory through the end of the year, with a return to positive growth not coming until the second quarter of 2017. They also reported that the Institute of Supply Management’s PMI, a key measure of manufacturing’s health, dropped to 49.4 in August, which indicates contraction.

WHERE IT GOES FROM HERE

All of these shocks to manufacturing demand will probably continue to cause more deceleration of business activities throughout the manufacturing value chain rather than growth in many market sectors this year, with many forecasts predicting only 1.1 percent overall growth in manufacturing in 2016 (which is essentially none) and only 2.4 percent growth in 2017.1 So nobody really knows what lies ahead, however, MAPI reports that there are some market sectors to keep your eyes on that might turn out to be quite strong:

What Could Be Hot

New housing starts could grow at a very rapid pace in the next three years because they remain at a low level relative to the pace of expected household formations. The 2017-2018 growth rates could favor single-family starts, as multi-family starts could grow at a slower pace after many years of leading the housing recovery. The housing supply chain (wood products, nonmetallic mineral products, HVAC, household appliances, furniture, etc.) could continue to ramp up for three more years. Some predictions from MAPI as of this writing include:

- Housing starts: up 16 percent

- Household appliances: up 5 percent

- HVAC: up 4 percent

Health care is a growth business. An aging population and the ACA could drive demand. Pharmaceutical production is growing again in the U.S., owing to new blockbuster patent-protected products. Medical equipment and supplies production is currently constrained by the consolidation of hospitals, insurance companies, and physician practices, so opportunities exist to fill manufacturing capacity. Some MAPI predictions:

- Pharmaceuticals and medicine: up 3 percent

- Medical equipment and supplies: up 2 percent

Mining and drilling equipment production could bottom out this year, but as commodity prices rise higher so could production growth, particularly in mining and drilling equipment. Some MAPI predictions:

- Mining and oil and gas field machinery: up 5 percent

Electronics, controls and communications equipment could increase with the growth of the Internet of Things in every facet of business, nutrition, transportation, exercise and entertainment. Some MAPI predictions:

- Communications equipment: up 4 percent

- High-tech computer and electronic products: up 3.1 percent (and perhaps 5.3 percent in 2018)

Other Sectors

- The growth streak of motor vehicles and parts production may begin to taper off in 2017.

- Private commercial and non-industrial construction could post relatively strong growth rates during 2017-2018. Industrial construction could decline sharply in 2017 and 2018. A surge in new transportation and chemical plants appears to be ending. Public utility construction could decline in 2017 and 2018.

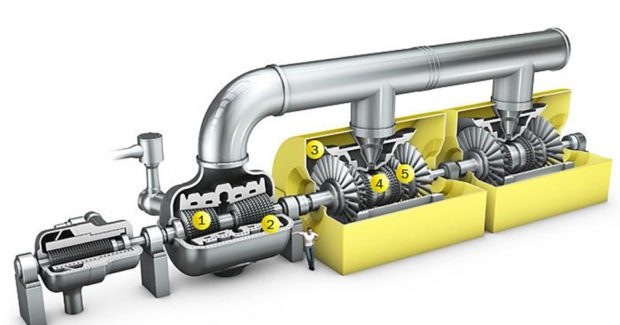

- Total machinery production could post growth of 2 percent in 2017 and 4 percent in 2018. Agricultural, construction, drilling equipment, engines and turbines could all start recovering in 2017. Commercial and service industry machinery and HVAC equipment could consistently post moderate growth over the next three years.

- The slow pace of manufacturing growth, the strong dollar, excess capacity in China’s manufacturing sector, and low commodity prices could significantly hurt steel, alumina and aluminum, and fabricated metal products production.

- The aerospace industry appears to be slowing. Most airplane deliveries are now to foreign buyers. The decline in commodity prices, the slowdown in China, and the strong dollar continue to hurt deliveries, despite huge backlogs.

“Manufacturers are feeling cautious about the economy and hesitant to make new investments until they get a better sense of certainty,” noted AMT president Douglas K. Woods. In other words, as we prepare for the New Year, these are both the best of times and the worst of times for the business of manufacturing. But keep looking up, because as fast as things are changing now, the next spring of hope is just around the corner.

Please note that this research was assembled from data and analysis produced by:

1 Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation (MAPI; Arlington, VA)

2 Precision Metalforming Association (PMA; Independence, OH)

3 AMT – The Association for Manufacturing Technology (McLean, VA)