May the Press Force Be with You: Tips and Tricks for High Tonnage Bending

Bending thick plates requires more attention to certain details than lighter bending jobs. Here are some ways to get all your ducks in a row before you bend the first part, so that your job will go more smoothly and translate into more profitable production.

Posted: January 2, 2019

Bending sheet metal parts with a press brake can be a rather tricky proposition, especially compared to most other manufacturing processes. There are many variables that come into play when you take a piece of flat metal and form it into a 3D structure. Invisible stresses in the part to be bent can manifest in all kinds of surprising ways once you start stretching and compressing the material during forming. Press brake operation requires careful selection of tooling for the job at hand, careful planning in the sequence of bending operations, and consideration of physical factors such as part whip and how to back gauge a flange accurately with repeatability. Even after all the work to prepare and setup a bending job is done, extreme care is required in the actual forming process: Because of how closely press brake operators interact with their machines, the potential for a mistake to lead to serious injury is an ever-present risk.

All these factors come into play even for the tiniest of bent brackets, but when we start to consider bending thick plates at high tonnage loads, the picture becomes even more complex. Let’s take a closer look at some basic considerations to keep in mind when you tackle high-tonnage bending jobs, as well as some tips that might make your heavy plate bending operation a little bit easier.

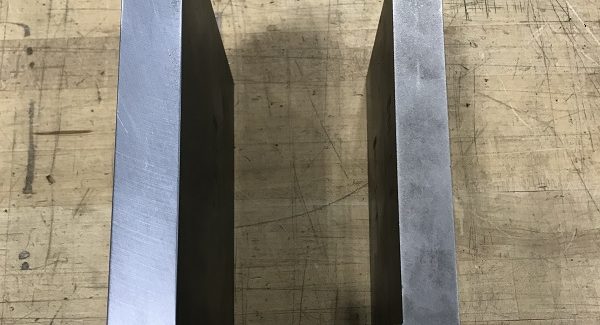

Like any bending job, the first point to consider when taking on plate bending is the tooling to be used. Most sheet metal fabricators who are familiar with bending have heard of the rule, common in airbending operations, that the opening of the V-die should be at least six times the thickness of the material to be formed. When we get into high-tonnage and thicker materials, this rule often needs to be modified: From around ½ in thick and up, it is recommended to consider eight times the material thickness as the minimum V-die opening. The radius of the upper tool also becomes more and more important as material thickness increases. The ideal punch radius for any given bending job is around one material thickness, but in thinner sheet metal this correlation can largely be ignored. When you get into plate materials, say from ¼ in thick and up, bending with a punch radius that is too sharp can cause serious problems.

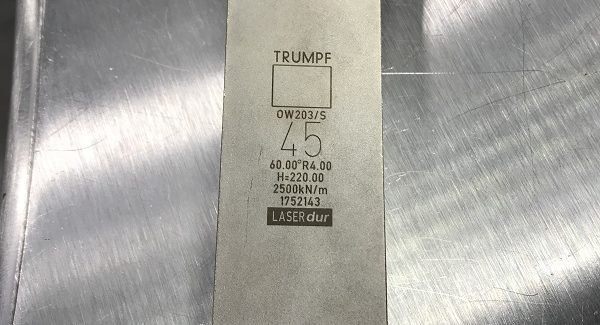

The first and most obvious problem is cracking of the material along the bend radius: This is caused when the stretching of the metal overcomes its elasticity, and instead of deforming in an elastic manner like it should, the metal fibers begin to shear and separate from each other. Obviously, bent parts with cracks are not good from a product quality standpoint, but this can also be an indirect indication that you are putting too much pressure on your bending tool: That sharp punch tip is taking more friction than it probably should be, which could lead to premature wear of your expensive tooling. When considering tool selection, it is also important to understand the force rating that every press brake tool is assigned by its manufacturer. When you start bending thick material at relatively high tonnage, those force ratings become real critical really fast.

Anyone selecting tools for a press brake job, whether it is a machine programmer or a machine operator, needs to be able to handle the basic calculations to determine if a bend is within the limits of the selected tools. If we have a tool that is rated for 25 tons per foot, and our plate to be bent is four feet long, then the force we apply to the part must be no more than 100 tons or we risk severe damage to the bending tools and dramatically increase the likelihood of injury for the machine operator. Make sure you understand the force ratings on your tools and how they compare to the part you are making, then check the tonnage that your NC program is calling for before you ever hit that foot pedal and trigger the first bend!

In most forming jobs, the tooling is the “weak point” in the bending process – and that’s the place where you will normally see a problem if you are applying too much force, i.e. broken or deformed brake tools. However, the press brake machine itself may also have some physical limitations that become apparent when you apply high pressures. Most modern press brakes generate force using hydraulic cylinders, and due to design considerations when you build a press those cylinders are typically mounted at the outer left and right edges of the machine where the frame is the strongest and most capable of handling the pressure load. Since the pressure the machine can generate comes from both cylinders, left and right, it means that each side of the press brake is only generating about half of the overall force. This means that if you bend your plate off-center (more to the left or the right side of the machine), you may not be able to generate the full pressure the machine is rated for.

So – when your bending job calls for more than 50 percent of the rated tonnage of your machine, you need to be bending at the center of the brake to ensure you get full pressure on the part and don’t stall the machine.

The tool clamping on the machine is also an important factor when the pressure gets high. Every press brake tool clamping system also has a force rating, like the bending tools, which will be expressed in tons per linear foot. Consider a press brake with 350 tons of pressing force capacity and a tool clamping system that has a rating of 75 tons per foot: If you are bending a heavy plate part that is two feet wide and you are using 200 tons of force, you are nowhere near the limit of the machine’s capacity, but you are way over the limit for the tool clamping itself. Proceeding with the bend at that point can damage the tool clamps, which probably means that a costly repair bill is headed your way.

There are also some methods to alleviate the required pressure when you get into forming thick plates. Going to a larger V-die opening will drive the required tonnage down, but the bend radius or flange length requirements for the part may not allow much wiggle room in that regard. One solution that is tooling-based is a V-die with rolling shoulders: Some tooling manufacturers offer these types of tools specifically for bending thicker material at higher tonnage. A V-die with a hardened dowel rod for a shoulder that can roll while the bent plate drags over it reduces the friction between the part and the tooling and thereby reduces the tonnage required for the bend compared to a solid tool. This style of tool will probably be more expensive than a solid die, but the reduced wear and tear on the tooling and the press brake can justify the investment if you will be bending thicker materials often.

Another way to achieve the same result without special tooling is the use of a heavy-weight lubricating oil. Liberally applying heavy oil to the shoulders of your solid V-die has the same effect as the rolling shoulder tool: The friction generated during the bend is minimized, which can reduce the required tonnage to make the bend by as much as 10 percent. Although this does mean your bent part will get oily and may require cleaning, this is a good way to handle the occasional plate bending job without beating up your machine and tools. At the end of the day, bending thick plates requires more attention to certain details than lighter bending jobs, but the overall goal should be the same: Get all your ducks in a row before you bend the first part, and the job will go more smoothly, which really translates into more profitable production.